Reflecting on the differences between Data Engineering vs Software Application Engineering

Photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash

What makes working on Data Systems different from working on Applications? This is my experience.

Everyone who builds software products, works with data and code but in a different ways. When I started out in Software Development, which at the time was more general than it is today, what I was actually doing was Software Application Engineering. I worked on a client-facing system for people who used the web application to set-up and sell insurance products, generate documents, email their clients etc. We developed all the features of the product across backend and frontend. I later moved onto a system that processed lots of accounting data. It’s frontend consisted almost entirely of tables and offered the challenges of determining how to process more and more data across distributed services, optimising SQL queries and generating data that went to a ‘downstream’ system. It didn’t have this name at the time, but I was doing Data Engineering work.

Throughout my career I have gone between these kinds of software products and have found that although the work for these products certainly has its similarities they are not the same role. It’s been interesting discovering the subtle ways in which Data-Engineering and Software Application Engineering are different. Below are a few of the things that I’ve personally experienced over time.

Sets vs Objects

Although guaranteed to spark debate, the fact is that most modern user applications are written in structured Object-Orientated (OO) languages like Java and C#. Some non-OO languages have even developed OO mechanisms to participate in an OO world - like Python adding classes. Objects that interact with each other in a domain is a useful way for a programmer to design behaviour and keep track of state in a system. But the other way around (Functional abilities in OO languages) developed too - like lambdas & streams in Java and Linq in C#. Why is this?

In User apps that model domains, objects make a lot of sense and designing objects that interact with each other can be helpful when you’re trying to understand how everything in the domain fits together and behaves. For data-processing engines however, these objects feel awkward.

Do the objects processing and transform themselves? Their child objects? Even though you can use OO languages to write processing engines, and many have, the code tends to evolve into services that hold the processing logic and domain objects that have little to no behaviour (we called them Plain Old Java/C# Objects, though I’ve seen them referred to as ‘data classes’ in modern frameworks). Simply put - it’s easier to organise the logic in this way - there is a natural flow of transformations. It’s much easier to understand collections of data onto which Functions are applied, to create a new data set.

In the Functional-programming paradigm - the programmer is actually working with data sets and functions and not with domain objects. It’s worth understanding both paradigms because when well written, they can play really well together in the same codebase.

User Stories offer less technical insight

User Stories for an end-to-end feature ideally look something like this:

As a customer,

I want a colour filter on in the left panel,

So that I can filter for all purple products.

This encompasses at least placing a panel with colours on the front end, sending the selection to the service API, performing a selection on the database and returning the product subset in a list. There could be performance challenges here like loading paging so that the page doesn’t hang while loading all the products, asynchronously loading all the product pictures but ORM tools usually handle a lot of the potential problems for you and you tend. You may break this down into tasks but you probably don’t unless there are complicated interactions with your APIs.

Trying to write end-to-end stories around data usually turn out like this:

As a[n] analyst / data scientist / operations / pretty much anyone in the business

I want to add this value to a filter / pull in this data / be able to breakdown data in a certain way

So that I can pull a report for [some business reason].

Although we are trying to be diligent in our User Story writing, if we’re honest, our data pipeline stories often drift into this templated pattern of “I want some data in a certain way” so that [I can perform some business function].

It may give us an understanding of why we are building a new feature or moving around data, which is useful, but it’s not very useful in helping us understand the ‘how’ behind making this request happen. It’s almost impossible to try and size a story like this. It’s an ‘iceberg’ story. There is so much that the user doesn’t see. The scaling, processing, data modelling, changing the data feeds in the pipeline, updating queries… all to bring one more field to the front end for selection and display. I find that it’s better to leave this story at Epic level and break down technical stories that will be required to build the feature. This is much better for the team as they’ll better understand the scope of work and they can see smaller pieces of work getting completed (moving across the board) instead of only moving a story weeks later when you’ve actually built the required report.

Data lives across the business

On a Product team you will gain in depth experience into the functions of the business that your product touches but unless you’re in a very small company, there will often be multiple products and you’ll tend to have a core set of users that your product is designed for. You won’t have much interaction with other departments of people that don’t use your product.

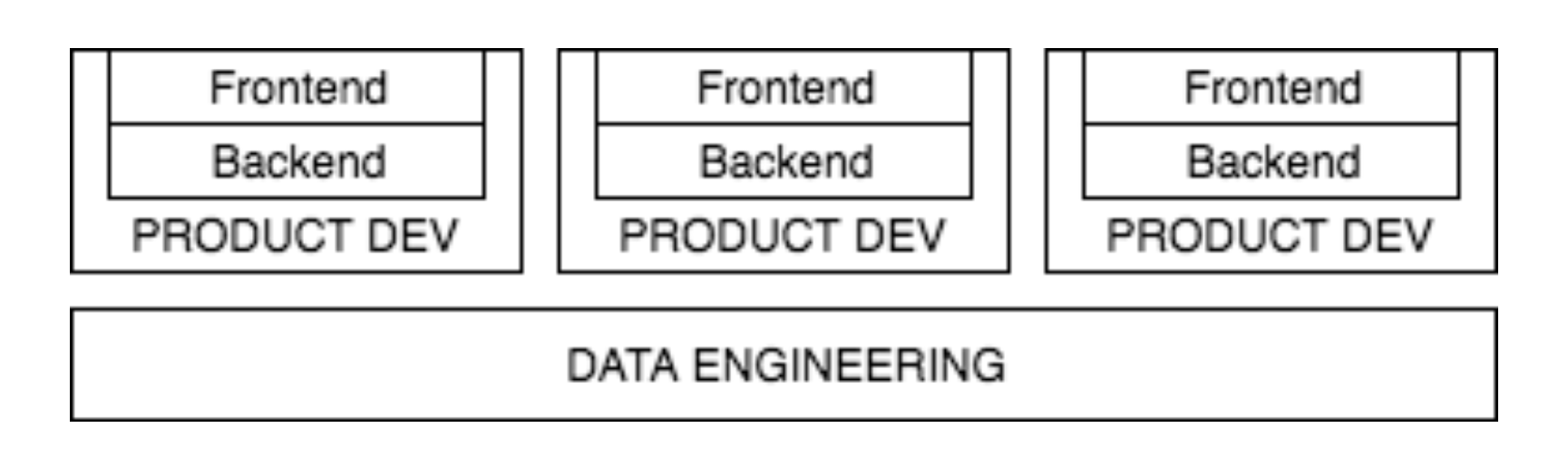

Modern Data teams work across multiple business functions, often across multiple product teams, if not across all products. The diagram below illustrates what I mean:

This can mean that your data team is involved in almost all feature development that goes on in the products across the company, as inevitably someone needs to store or retrieve data that flows through your teams pipeline(s).

This can be really interesting if you like having more knowledge about how the company works overall but can be frustrating for people who prefer to focus on a smaller subset of the business. It also presents challenging priorities as you need to balance the priorities of work coming from lots of product teams as well as your constant technical enhancements that inevitably continue because you’re generally storing and distributing more and more data, which brings along technical challenges.

Plumbing vs Crafting

As an app developer, I worked on tasks that were either new front-end features or business rules in backend systems. At some point it would be time to connect the code to the rest of the world and integrate with an API /database /other external system. Sometimes this could be a couple of days of integration work - setting up keys and credentials, figuring out the API client, writing exception handling for inevitable failure of said API… But, once done, there’s hopefully a nice, neat interface wrapped around it and this invasion does not upset the well crafted code.

For Data Engineers, integration is life. The difference for me is that sometimes a piece of work can be purely integration. There is no specific business driver involved in the change besides maybe continued business growth (read: more data). You’re not building a new feature like displaying new content, using a new algorithm or providing a newly designed interface to users to improve retention. You’re simply putting different systems and data stores together because data needs to move to or from these systems/stores and it needs to do so more and more quickly. I say simply, but it turns out that this can be quite challenging.

Some examples of data-engineering work includes: connecting to other systems to retrieve or deliver data to; handling the bad data (by probably storing it in a queue or file system for inspection, correction and re-play); building in re-tries; tweaking configuration files and garbage collector settings and changing architecture to handle data load; managing memory and disk set-ups so the machines doing the processing are optimised…

I refer to this as plumbing. I envision twisting pipes together, adjusting notches and possibly tweaking multiple parts of a physical pipeline at the same time. The metaphor of a physical pipeline with water flowing through it, really embodies, for me, the data pipeline work that engineers do. If you’ve ever lived or worked in a large building where the plumbing wasn’t working correctly and had the plumbers come by and fix something, only to have a pipe burst on the other side of the building, then you’ll have some empathy for data pipeline work. You can often be building across the entire pipeline at the same time as you make changes to certain parts.

Simply, although you do also write logic to parse and model the data and you can craft good code here like any other developer, there is less of this type of work than there is infrastructure/plumbing work in Data Engineering. I wrote more algorithms in C# (ie application/business logic) as a backend developer than I do now.

An app developer will focus a fair amount on the logic and design implemented in their application and integrations are a necessary nuisance which get dealt with every now and then.

TDD

Related to the previous point, sometimes you can drive code from the business rules given (inside-out TDD) but when dealing with data, the surprises are more often in the actual data than in the rules. When writing data processing code, it can be more useful to write integration tests first. In other words. It’s often more useful to write a test that creates a service class, reads in a file and returns the expected output first, and write the smaller tests as you go along. Especially if you’re not sure what data issues you could be dealing with.

Metadata

Something that never came up in user applications that I developed was the idea of useful metadata, that should get stored with the data. It was only when I moved to data-focused systems that I realised the extra information one can store with data that helps provide data auditability, lineage and even trouble-shooting help. Metadata like: the version of a record, if it’s been updated; a timestamp of when the record was written, etc; what service it came from and other information on the record that came from other systems. Storing this data is not second nature to app developers but can be gold to Data Engineers who care about how data is travelling through the ecosystem of a company (and beyond if possible!).

Infrastructure and Optimisations

All engineers need to be aware of the infrastructure their code is running on if they want it to work well. In companies that have embraced a DevOps culture, you’re likely working more closely with infrastructure than you ever have before.

I have realised however, that the Data Engineering work I now do has a much larger ratio of infrastructure to feature development work than application development work did. There can be weeks where my team and I are working on optimisations for the same piece of processing because there is often just simply more data that needs to be processed, or it needs to move more quickly through the pipeline. Also, tweaking one thing in the pipeline, often affects another service or data feed along the pipeline (sometimes even upstream!).

There is also an awful lot of infrastructure components involved at big data loads which contributes to the higher ratio of infrastructure building and optimising in Data Engineering versus feature development for applications.

Conclusion

Data-engineering is a new specialisation and is not completely different from application engineering but it comes with different paradigms and challenges. Understanding the differences on both sides will ultimately help both roles work together better (your metadata will thank you!). And it’s also worth knowing that it’s possible to go between both roles if you feel like a change or challenge!